Pakistan’s film industry would complete its 75 years this year, and its history is quite fascinating. Talented people from all over the country have given their sweat and money to the filmdom, which was in a bad shape at the time of Pakistan’s independence. Despite its giant strides during the first 50 years, many promising Pakistani films couldn’t see the light of the day, and had they been released in cinemas, who knows where Pakistan’s film industry might have been today.

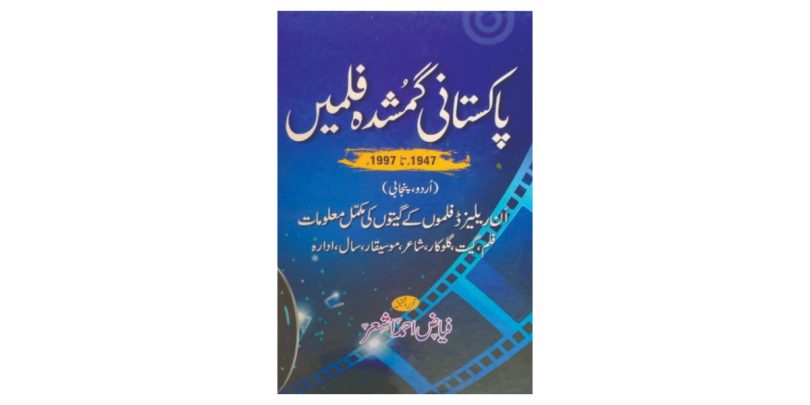

Researcher Fayyaz Ahmed Ashar’s Pakistani Gumshuda Films (The Lost Pakistani Films) is one such book that brings those ‘unreleased’ or you can say ‘lost’ films to the public. Its biggest advantage is that it is in the very language most of the films mentioned here were made – Urdu – which gives it a bigger readership scope. In a country where only a handful of books on films are available, having this book in your collection is nothing short of a godsend.

A lot can be learned by just going through these pages where all films that weren’t released have been mentioned alphabetically, along with the creators behind their soundtrack. Why does this book only mention the soundtrack is because, in India and Pakistan, there was a custom that film songs were released long before the film itself so that the listeners would mark their calendars for the film’s release, if and when it was released.

This book is intelligently divided into two parts – Urdu and Punjabi films – because they are the most-watched films in the country. Other regional film industries can’t be compared to films made in these two languages and that’s why the author took an informed decision and went ahead with it. Now readers who are interested in either language would begin with that language and will not have to skim through pages to find the films of their choice.

Although the title of these unreleased films is mentioned from alphabets Alif Mad Aa to Bari Yeh, there are a number of ways to read this book. Since the playback singers, lyricists, and music composers (besides the name of the production company) who were part of those soundtracks are mentioned in table form, you can pick your favorites and search for their names individually. It could be Ahmed Rushdi or Noor Jehan from the playback singers’ column, music composers Khawaja Khursheed Anwar or Robin Ghosh from the music composers’ column, and Qateel Shifai and Masroor Anwar from the column where the names of the lyricists are mentioned, or you can just read the film’s name and follow the songs just like they are presented.

If you didn’t know that a handful of film songs by music composer Sohail Rana haven’t been released to date, or that some of the famous songs that we have heard were initially supposed to be part of a film, that couldn’t be released for various reasons. The patriotic song Chand Roshan Chamakta Sitara Rahay was part of a film titled Mujahid-e-Azam (1951) and was sung by Dilshad Begum; Noor Jehan and Mujeeb Alam’s Khuda Kabhi Na Karay from Anjana (1972) was aired regularly on Radio despite the film’s unreleased status, and renowned Indian singer Talat Mehmood and Mukesh also sang a handful of songs for a Pakistani film that couldn’t be released.

That’s not all, films that were produced in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) also get mentioned here because, before 1971, the two wings were one unit, one country. And just like the ‘lost’ Urdu films and their songs, the writer also works diligently to come up with a list of Punjabi films, the songs of which were released but the films weren’t. You can follow the same process of searching for your favorite singer-music composer-lyricist or read along as intended, but one thing is sure that you will not be bored since every page is a treasure trove of information regarding ‘lost’ films and their music.

At the end of the book, there are pictures of the posters and/or gramophone records that have helped the author in compiling this amazing book. The record is up-to-date for the first fifty years – from 1947 to 1997 – and contains songs that you might have believed were part of a released film. However, some of the entries have issues with either the release dates, the title of the songs, or the names of the music composers. At one place the name of Nisar Bazmi is mentioned as Nisar Bari, while at another place, music composer Wajid Ali Nashad’s name is mentioned in a film released in 1970, when in fact he began his career in the late 1970s.

Similarly, the film Naghmat Ki Raat which featured an Ahmed Rushdi – Akhlaq Ahmed duet is said to have been released in 1965 which is wrong because Akhlaq Ahmed broke into the film industry in the 1970s. Another entry has Shazia Manzoor’s name present in a film released in the 1980s, when in fact she participated in the Music Challenge in the 1990s before making a name for herself in films and non-film songs.

I hope that the author corrects these mistakes in the next edition so that when he does update the book for 75 years, he comes out with an error-free guide, that can shine ahead for many more years to come. On the whole, this book is a must-have for film buffs and can help you with many things. In fact, it told me that a number of songs by the Zameen Ki Goad famed singer Mohammad Ifrahim were part of unreleased films and that lyrics of one song that was already produced in India were used in a Pakistani film, by the same lyricist Shewan Rizvi who had penned those words across the border. Interesting, isn’t it?