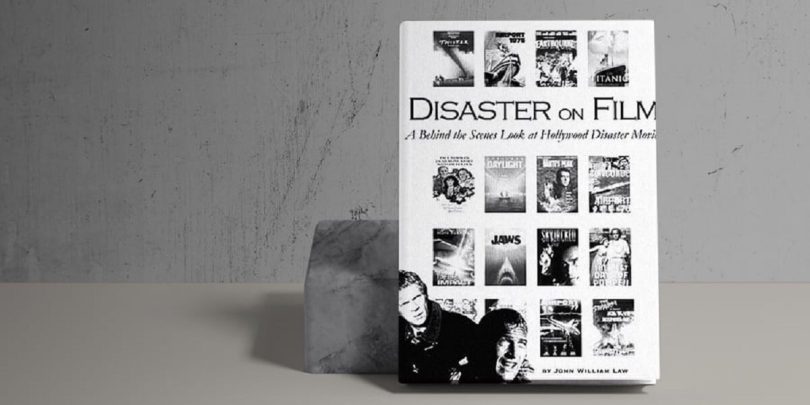

The history of Disaster films has been as old as the history of films itself. Directors all over the world have been using destruction, aliens, and calamity as tools to shock the audience since the early days of Hollywood. However, John William Law’s Disaster on Film takes the readers through the ups and downs of Disaster films and makes you wonder where they will strike next.

Through this book, fans of the disaster genre will be taken behind the scenes of Hollywood’s major disaster films from the earliest days to the flicks in the new millennium. It not only discusses their fate at the box office but also the reasons that made them great. However, it doesn’t end there for it also tackles the reasons behind the failure of sequels to some of these films, and why the disaster genre couldn’t survive past the 1970s.

If Airport breathed life in the genre and The Poseidon Adventure was a smash hit, then why didn’t their sequels follow suit; how were Deep Impact and Armageddon impacted by ‘help’ from outer space before their release and how the genre was resurrected after a quiet 1980s, this book tells you all there is to know about disaster movies. That’s not all, the readers get to know of the changing formats of the genre, that at one time depended on big names, but now their success depends on perfect execution.

From ‘Disaster in the air’ to ‘Disaster on the high seas’, this book covers them all with ease. It beautifully explains why the disaster genre isn’t considered a separate one like adventure, romance, drama, and action, and why the repetition at times pushed the audience away instead of attracting them towards the movie. The major difference this book correctly points out between the Disaster flicks of the 70s and today is that back then, the big names were the stars, and today the special effects are.

Don’t be surprised to know that the earliest disaster flick was made way back in the 1910s, but it wasn’t until the 1950s that producers got seriously involved in the genre. There was a Titanic in 1953 before James Cameron’s version in 1997; there was a War of the Worlds the same year as the earlier Titanic before Steven Spielberg and Tom Cruise teamed up for their version in the new millennium; Alfred Hitchcock’s Birds was the first movie to use animals as the villains, long before Jaws normalized it.

Be it The Towering Inferno, Independence Day, Daylight, Titanic, or The Day After Tomorrow, this book dissects every notable disaster film in order to make the readers realize how these successful films met the commercial demands of contemporary Hollywood. Some changed the way disaster films were made while some failed to cater to the audience because of the shortcuts the filmmaker took to complete the project. This book explains how those films that tried to be different succeeded and why those who followed the set pattern, faltered.

And then there were the filmmakers who helped the genre rise and fall in the 1970s. If Irwin Allen was the man behind two of the biggest hits in the 1970s – The Poseidon Adventure, and The Towering Inferno – then he was responsible for the biggest flops too, namely The Swarm and Beyond The Poseidon Adventure. The same decade saw the end of Alfred Hitchcock who didn’t do much and the rise of Steven Spielberg who made people fear the ocean because of Jaws.

The book credits Twister as the film that revived the genre and made filmmakers realize that if they treat the disaster with respect, the viewers will respect their effort. He mentions the names of those big-budget movies that derailed the genre, including Bug, Avalanche, and Meteor, and how improved ‘special effects’ changed the course of the way disaster films were being conceived and executed.

Disaster flicks – according to this book – have seen it all, threats from outer space to those from down below, and as per the author, it’s time that the makers try something new. The author, who should also be commended for covering films from all eras, chronicles disaster films and tells the readers that such films can only sustain if they don’t bore the audience. The way he discusses each and every disaster film in this book shows his grip on the subject, and the way he combines the good elements and the bad – towards the genre’s development – will please the readers.

The film stills or images within this 200-page book might be its weakest link, but who needs them when the whole story is in front of you. From the first page till the last, the text in this book adds colour to the usually dark-themed disaster genre and helps the readers understand that there is more to disaster films than meets the eye.