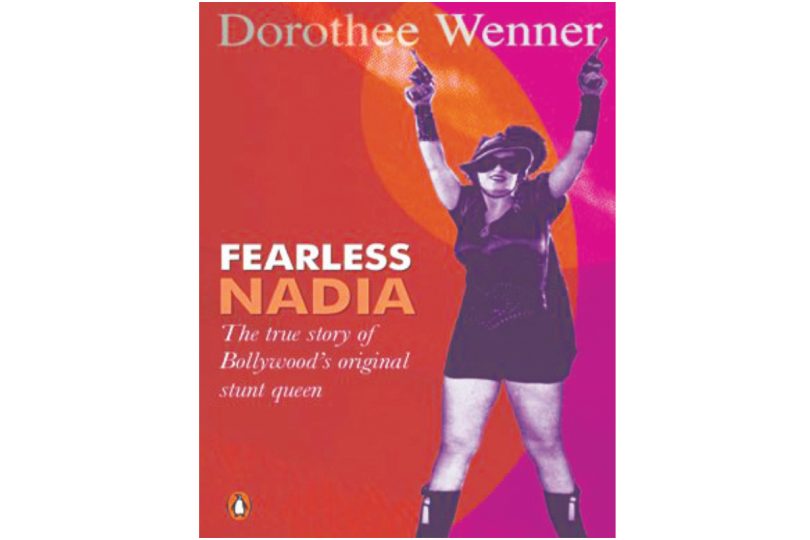

How Mary Evans whip-cracked her way towards stardom and became Fearless Nadia in Bollywood

Wearing a mask, she rode horses onscreen when women weren’t allowed to act in films; she sent men flying with a thwack long before an angry young man did it forty years later; she ran atop trains when it was considered suicidal for even stuntmen. Why? Because she was Fearless Nadia, the first action star of the subcontinent who even today is considered an iconic figure, in both Indian and world cinema. Fearless Nadia is a tribute to her legacy and there can’t be a better time to revisit the past than the month in which she was born as Mary Evans and passed away as Fearless Nadia.

This definitive biography of Indian cinema’s most unusual iconic figures was penned by Dorothee Wenner in German and was later translated by Rebecca Morrison for readers in the Indian subcontinent, and it is nothing short of a treat. Not only does it trace back the roots of feminism in Indian cinema but also talks about the person responsible for that. It begins with the journey of a young blonde girl in the mid-1930s who wanted to look after her family and ends up with a blue-eyed woman who swung on chandeliers, sported a mask, and lived in the hearts of all those who paid to watch her win every battle.

This book tells the readers about the origins of Mary Evans who went on to become the Hunterwali in India, how she came over to India from Australia, why she chose acting or acting chose her, and how she changed the way cinema was seen in her prime. Her tight-fitting shorts and brandishing whip added to her aura that drove audiences into raptures and gave stunt films the kind of push they needed to entertain audiences.

From the mid-1930s till the mid-1950s, Nadia was the top film star in India, and even though she wasn’t proficient in Urdu/Hindi, she let her hands, feet, and eroticism do the talking. According to this book, she was one of the first film actresses in India to wield revolvers, play with lions, and show the world full of men and women that nothing is impossible. Had it not been for her, filmmaking in India wouldn’t have taken the giant strides it did, and it would be fair to say that Bollywood as we know it today wouldn’t have existed without the fearlessness of a foreigner who was raised in the country.

Be it her initial struggle as a foreigner in India, her ability to do things only reserved for men, and her insistence to take up challenges, nothing misses the author’s radar who combs through her career with a microscope. How her ‘Heyy’ became popular is what the author touches on as well, but not before taking the readers through her struggles in the entertainment industry. Had it not been for her street smartness, she might not have managed to make inroads into the movie business, the scenario which is mentioned in this book.

If you had no idea that before she became Nadia, Mary Evans toured India as a theatre artist and even spent time at a Circus, that she changed her name to Nadia on the insistence of an Armenian fortune teller, and that she loved doing her own stunts long before stunts became common, then you have to read this book. It also explores the relationship of the Wadia Brothers who introduced Nadia to films, with the younger one marrying her when she wanted to settle down later in her career.

Why was she nicknamed Hunterwali you might ask? Because the first film that brought the wild side of a wannabe actress to fore introduced her as Hunterwali, who wielded a whip long before anyone else did on the screen. That one hit changed her fortunes and made her the box office star and her backers – the Wadia Brothers – into successful filmmakers. This book explores the trio’s highs, lows, parting, and reconciliation perfectly, and intrigues the newer readers to find out more about the daughter of a Scottish-Australian soldier and Greek belly-dancer who ruled the male-dominated universe as a boss.

Not only does the summary of her hits like Punjab Mail, Diamond Queen, Jungle Princess, and Bombaiwali get mentioned in this book, the impact of these films on her future as well as that of Bollywood is discussed as well. Her retirement in the 1950s and her comeback when she turned 60 are explained as does her ability to give a tough time to her male co-stars who were mostly pushed to supporting roles in her presence. The book explains to the readers how Nadia inspired girls from respectable families to venture into films while the scattered pictures give them an idea of how she managed to embrace the culture she wasn’t born into.

Since the writer wasn’t a native of India, she discussed things on the sidelines too much, which could have been edited in the English version. A book about Fearless Nadia should be only about him but somehow the writer included the rise and fall of the Wadias in it, alongside the Independence movement, and the resurgence of female prime ministers in the region, which she believes was the result of the Nadia effect. However, she compensated for that with the interviews of all those who had been part of Nadia’s career and had seen her achieve impossible feats without the help of stunt coordinators. On the whole, this biography should be in every film buff’s collection because it tells them that whatever is happening in films today wouldn’t have been possible had a certain Nadia not been fearless.