HIP talked to Rameez Anwar and Zeb Bangash about their stellar collaboration!

OMAIR ALAVI PUBLISHED 12 AUG, 2020 04:09PM

There was a time when Pakistani film music was loved and appreciated by all, be it the masses or the classes. That was the Golden Era of Pakistani Film music when Khwaja Khursheed Anwar, Rasheed Attre, Master Inayat Hussain, Feroze Nizami and other music directors were at the helm. Their songs are even loved today more than fifty years after they were composed, and their work is still recognizable due to its originality, finesse and diversity.

Even today, whenever a song that takes the listeners back in time is released, it generates a lot of buzz, because it provides the fans of the bygone era a trip down the memory lane. Be it Fuzon’s Khamaj or its many inspirations, they release to a thunderous applause each and every time.

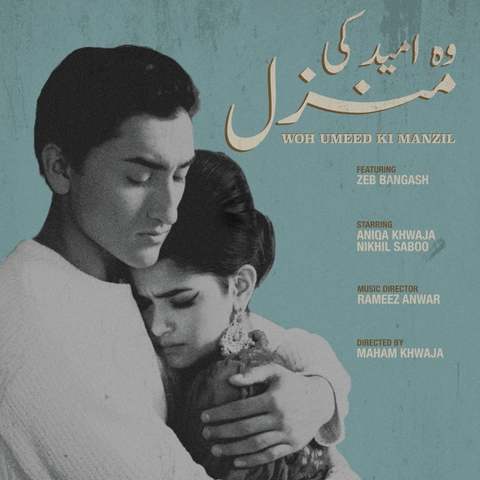

That’s why when the grandson of Khawaja Khursheed Anwar – Rameez Anwar – collaborated with Zeb Bangash and came out with ‘Woh Umeed Ki Manzil, everyone loved the feel behind the monochromatic music video, the grand composition, the heart-melting poetry and above all, Zeb Bangash’s novel style of singing. HIP managed to talk to both the composer Rameez and singer Zeb about this collaboration and they had a lot to say how the song was conceived and why they decided to come with a music video that had nothing in common with the present, but everything in common with the past. Excerpts:

HIP: Rameez, your song seems like a perfect tribute to the era when your grandfather was on top of his game. Was coming up with a black and white video a deliberate decision to give it the vintage touch?

Rameez Anwar: Absolutely. When Maham Khwaja (another of Khwaja Khursheed Anwar’s grandchildren and a filmmaker) and I first began discussing the project, it was assumed that we would be doing this in black and white. There was no other question. Although after we filmed the video, we were very very briefly tempted to use the color footage, since the fall colors in the garden were in full force, making for a very picturesque setting. However, we stayed the course and stuck with the black and white color grading (along with some digitally added graining to give it that less sharp look of older films). We wanted it to feel like you were watching some lost footage from a 50s-60s film. Like Ghunghat or Intezaar; so the black-and-white was an almost automatic choice.

HIP: What made you go for a romantic filmi song in an era when people are into fast numbers?

Rameez Anwar: It is a bit of a paradox. A lot of contemporary music these days can sound homogenous, even if an artist is trying to do something new. In a way, by reaching back for these old, traditional methods of composition, I think I have been able to present something to audiences that feels simultaneously very familiar, and yet, very unique for this day and age. “Everything old is new again,” as they say.

For me, I look at examples here in the US and in Pakistan that show that people still yearn (at least every now and then) for traditional expressions of art. We see it a lot with some of the most successful songs from Coke Studio’s repertoire. In America, you have films like La La Land, or even better, The Artist, which was shot as a black and white silent film and which was critically and commercially successful. These types of works of art offer a respite from the breakneck pace of modern life, and I think that’s a good thing that people yearn for. So for me, this was a way of offering people something different to break the cycle of standard music/music videos they’re seeing these days.

Even beyond that, I wasn’t overly concerned with how the public would respond to this song. Of course, I wanted people to enjoy it and I want this song to do well with audiences and critics. I wanted to bring some nostalgic joy into people’s lives. However, I can’t control the audience response. All I can do is to put in the work to make the song as good as it can be. My guiding ethos as an artist is to make music that I myself would like to listen to. If I can accomplish that, then I’ve done my work. I wouldn’t force others to listen to something that I wouldn’t want to listen to myself. That would be disingenuous. So again, I try to do that, make the best song I can make within my abilities and limitations, and then the rest is in God’s hands.

Zeb Bangash: Yes, fast numbers usually cause a stir, get popular quickly and artists want to have them in their repertoire. Personally I think they’re fun and I’ve thoroughly enjoyed the few I have sung in my career. Having said that, I am always on the lookout for ballads to sing and they have a special place in my heart. There is a lot more space for melody in romantic songs and as a vocalist I can really bring my emotive dramatic self. Also, as a romantic myself, I know that our people as an audience resonate with songs reminiscing on first loves and unrequited love. In my experience, these songs forge a bond with the audience that is personal and special and one that lasts much longer than a groovy dance number.

HIP: How would you rate the experience of working with a newcomer like Rameez Anwar?

Zeb Bangash: Rameez may have been a newcomer but he was highly accomplished as a musician and that was important to me. In any case I have met plenty of people who never ‘made it’ in the industry but are brilliant artists so my collaborators’ position in the industry is not a primary concern. With Rameez I found his work, his process and his artistic point of view inspirational and the minute I heard the melody for Woh Umeed Ki Manzil I was sold.

HIP: Rameez, tell us about the experience of working with Zeb Bangash?

Rameez Anwar: Working with Zeb has been an absolute dream come true. She is a true-blue musician, a genuine artist. She strives to be a better musician each day, and it shows. Her command of musical theory and her voice as an instrument is so impressive. She took a huge chance working on this song with someone like me who, aside from my Dada Jaan’s name, was relatively untested and unknown. So I’ll always be grateful to her for that.

When I arrived in Pakistan to work on the song, I made a list of all possible singers I had some personal connection to, however tangential, as well as a list of dream singers whom I thought would be out of reach but who would be perfect for this track. Zeb was at the top of that dream list. I did not think at the time that this was a realistic or attainable goal; I didn’t have the first idea as to who could put us in touch. However, fate intervened and an aunt of mine, Amna Zahid, put me in touch with Mr. Sharif Awan.

Mr. Sharif Awan was kind enough to meet with me, for which I’ll always be grateful. He asked me whom I had in mind for the song, and on a whim, I started off kind of embarrassed saying, “Well, I would love to have Zeb Bangash sing the song, but…” and before I could finish the sentence, he said “Okay done.” And he reached out to her and she was gracious enough to meet with me in Lahore, where we discussed the project at a broad level. She was intrigued, so I sent her a demo a little while after that. When she heard it, she immediately replied back saying she was in. I still remember how elated I was when I found out. I may or may not have run around the house a little bit to blow off all that excited energy. I knew with Zeb on the track, we would be able to work wonders.

I’ve been a huge fan of Zeb’s for years – ever since I first heard ‘Bibi Sanam.’ I actually attended a concert of hers in New York a few years ago. It was a magical evening, one of my favorite live performances. I was struck by her command of Desi as well as Western musical elements, something I picked up on in our first conversation about the song in Lahore. She’s got a very impressive and broad command of musical theory. I would be lying if I said I was not intimidated in that first meeting (laughs).

HIP: Zeb, your voice seems a little different in this song …was that a deliberate attempt to sound vintage or there was another reason behind it?

Zeb Bangash: I did not deliberately change my voice for this song but you’re not the first person to point out that I’m sounding different on it. To my mind there could be a few reasons why. This track was recorded and produced with a deliberately retro aesthetic, with entirely live instrumentation and lush arrangements. Perhaps, the lack of overly compressed brightness in the production is giving my voice a different character. Also the melody, phrasing and temperament of the song is unique and I haven’t heard this kind of composition before. Most significant is that I have been training my voice, which will always bring subtle changes in timbre and expression. I think it could be any or all these reasons. Personally I rendered the song according to the feel of the melody and the lyrics.

HIP: Rameez, your grandfather was a mentor to most of the music composers who came in the 1960s. Who mentored you when you were growing up?

Rameez Anwar: You know, I haven’t had one consistent mentor to guide me on this musical journey. If anything, I patterned a lot of my life choices off of Dada Jaan’s, though of course, I never met him as he passed away two years before I was born. I’ve studied western and subcontinental classical music, just as Dada Jaan did. I pursued academics and storytelling outside of music. Aside from Dada Jaan, one band I admired for a long time was Radiohead, and I’ve taken some lessons from their career arc. In addition, I’ve had many music teachers (piano, voice, sarangi) who have guided and shaped me as a musician.

And lately, I’ve been fortunate to be in touch with many musicians in the Pakistani scene who have been gracious enough to advise and guide me. I’m grateful to people like Omran Shafique, Asim Raza the lyricist, Sohail Abbas the producer, Javed Iqbal, Baqir Abbas, and Kami Paul, all of whom I’ve been fortunate either to work with or to get advice and guidance from or both. And, of course, Zeb has taught me so much, both as a performer and as a musician navigating the entertainment industry. So, I’m grateful to all of these fantastic and accomplished artists who have taken the time to guide me on my way.

HIP: Your grandfather was also a filmmaker… Do you have that in your genes?

Rameez Anwar: I do enjoy filmmaking and storytelling in other formats as well. Just as he was a screenwriter, I’ve devoted a lot of my time to writing short stories. A few years ago, I even spent a summer at the Iowa Writers Workshop, which is one of the premiere writing programs in the US. For a while, it looked like my career trajectory was headed towards a life as a writer. But then I switched course, just as Dada Jaan did. After all, he had a reputation at Government College of being a writer (mostly a poet), while his friend Faiz Ahmed Faiz had the reputation of a musician. They traded art styles, of course, and the rest was history.

As far as filmmaking, I’ve been heavily involved with directing and editing my prior work, and I’d love to return to filmmaking (and writing) someday. Though in the case of Woh Umeed Ki Manzil, I mostly stayed out of director Maham’s way other than a handful of spots where I had a long-held vision for a particular part of the song; after all, I’d been living with this song in my head for several years. However, the final product is overwhelmingly and almost purely Maham’s vision. She did a tremendous job researching all the visual details, developing a shot list, and executing her vision with her team (Brent Rowland as DP and Curtis Whitear as Production Assistant). I’m so proud of and grateful for the work she did for the video.