Omair Alavi|Sports|October 18, 2020

The all-rounders who couldn’t stay around for long

| If Test cricket mostly relies on specialist batsmen and bowlers, ODI and T20I cricket relies mostly on multi-talented players who are able to bat, bowl, and field well, usually in one match. Such cricketers are known as all-rounders, and currently Pakistan has a Prime Minister who used to be a top all-rounder in his playing days. |

It was due to the emergence of Imran Khan in the 1980s and of Wasim Akram in the 1990s as world-class all-rounders that many hoped to become one, and play for Pakistan. Many succeeded, and many failed and we will discuss those who couldn’t make it to the big league, despite the promise. Read on:

Shahid Saeed

He was a medium pacer like Mudassar Nazar, and a useful batsman who was comfortable batting anywhere in the order. But after making his Test debut alongside Waqar Younis and Sachin Tendulkar, Shahid Saeed is remembered as the unlucky one who couldn’t make it to the top. He did have a fifty to his name in ODIs, which came against India when he was asked to open the innings with Shoaib Mohammad. They scored 99 runs for the first wicket, and steered Pakistan to an unlikely victory. Despite having 13 first class centuries, 83 first class and 60 List A wickets and over 90 catches in both forms of domestic cricket to his name, Shahid played just 10 ODIs for Pakistan between 1989 and 1993, and a solitary Test against India where he scored 12, and didn’t take a wicket.

Wasim Haider

The only thing common between Wasim Haider and Wasim Akram besides their first name was the fact that both were part of the World Cup-winning squad in 1992. They were both all-rounders and that’s why Wasim Haider played less for Pakistan, as Wasim Akram was an integral part of the team in the 1990s. All his three ODIs for Pakistan came during the 1992 World Cup, and sadly, Pakistan lost two out of those three matches, with one ending in no result.

He did get the prized scalp of Ajay Jadeja for 46 that turned out to be his only international wicket, but most importantly, he was the third-highest scorer (after Saleem Malik, Mushtaq Ahmed) in the England match that gave Pakistan the one valuable point to qualify for the last four. His contribution was vital to the team, but even then he was out of favour during the mega event. He continued to play first class cricket till 2002-03, scoring six centuries and 26 fifties and taking 261 first class and 107 List A wickets.

Mohammad Hussain

He wasn’t the fittest cricketer around when he represented Pakistan in the late 1990s, but the burly Mohammad Hussain had his advantages. He could dispatch a good ball towards the boundary or out of the park, and wouldn’t make a big deal out of it. Nearly 45 percent of his runs (68 out of 154) in ODIs came from boundaries, and his ODI average of 31 and strike rate of 113 made him an ideal for the format. However, fitness issues combined with poor performance with the ball in Tests ensured that he didn’t represent Pakistan in more than 2 Tests and 14 ODIs.

His 13 ODI wickets couldn’t be labeled as bad performance; he just didn’t fit in the side that already had Saqlain Mushtaq, Mushtaq Ahmed, and Shahid Afridi. He is also remembered for his “invaluable” assistance to Inzamam ul Haq in Toronto because it was he who provided the bat to the gentle giant who nearly beat an Indian spectator who was calling him Aloo Aloo from the stands. It was commendable that he stayed there till the end for his “heavy brother”!

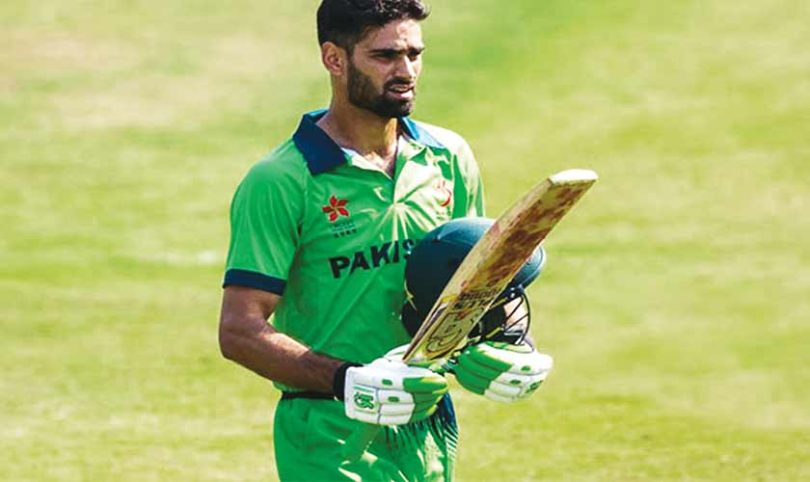

Hammad Azam

Close your eyes, think of an all-rounder who could have replaced both Azhar Mahmood and Abdur Razzaq and write his name on a piece of paper. Nine out of ten times, the name on the paper would be that of Hammad Azam, who came, impressed, and faded away. Although he is still just 29, it is tragic that he hasn’t been able to add to his 11 ODI and 5 T20I appearances for Pakistan. Yes, he took just two wickets at an average of 84.50 in his 11 ODIs, couldn’t go past 36 in his seven ODI and four T20I innings, but he managed six catches in his 16 international appearances, which is commendable considering our fielding standards. Had he been given more chances, he might have learned the tricks of the trade and showed why he is rated so highly in the domestic circuit.

He has scored more than 4000 runs in first class cricket at an average of 33, with six tons and 22 fifties, dismissed 181 batsmen in his 97-match career. In addition to all this, he has taken 61 catches and made a name for himself in List A and T20s circuit as an all-rounder. He should be part of the Pakistan set-up, which has given more chances to less talented cricketers. Hopefully, along with Bilal Asif, Aamir Yamin, and Hussain Talat, he would get another chance to prove his mettle and represent Pakistan for a long time.

Next Week: Wronged For No Fault Of Their Own – Part IV (Wicket-keepers)